There is a prevailing misconception that the reason Marxists call for public property has anything to do with a moral criticism of capitalism. In the minds of the critics, Marx was calling for a new ideal system based on a separate moral philosophy, therefore they accuse Marx of trying to build a “utopia.”

In reality, the Marxian argument for public property has nothing to do with ideals. While there are ethical criticisms one could make of capitalism — and many socialists do — Marxists stress that this is fundamentally not an adequate argument for moving beyond capitalism.

Economic systems are physical machines constructed in the real physical world, that produce and reproduce humanity’s means of subsistence over and over again. They cannot simply be constructed around vague moral philosophies and ethics any more than a computer can be built based on moral philosophy and not the physical and computer sciences.

“The Socialism of earlier days certainly criticized the existing capitalistic mode of production and its consequences. But it could not explain them, and, therefore, could not get the mastery of them. It could only simply reject them as bad. The more strongly this earlier Socialism denounced the exploitations of the working-class, inevitable under Capitalism, the less able was it clearly to show in what this exploitation consisted and how it arose”

—Friedrich Engels, “Socialism: Utopian and Scientific”

For example, in the work Anti-Dühring by Friedrich Engels, Engels responds to a socialist economic model proposed by Eugen Dühring. He demonstrates using economic theory that Dühring’s economic system was not only contradictory and could not actually work in practice, but would inevitably unravel itself over time and return to capitalism. In my other post here, I went into this in a bit more detail.

As we can see, simply proposing a system that sounds good does not mean it is actually compatible with the real world. All systems must, first-and-foremost, be based in rigorous economic theory.

Furthermore, the concept of constructing a utopia fails on other grounds. This is the grounds of historical materialism. Marx argued that humans construct their economic systems around the productive forces of society. Economic systems must be compatible with these productive forces, and these productive forces always change and develop over time. Therefore, the economic system itself changes and develops over time, since different systems are more compatible with different stages of economic development. I go into this in more detail in my other post here.

The fact we live under a capitalist society, which developed as a result of industrialization within prior feudal economies, is evidence in of itself that capitalism is an efficient way of organizing an economy around the current productive forces. Therefore, an argument that we must change our economic system should not begin with its conclusion, i.e. one should not start with what economic system they desire then try to find ways to make the world fit those desires. Rather, it should start with a rigorous and scientific examination of how the real world is, how it is developing, and therefore, what it is developing into. The conclusions, therefore, would be objective, and not subjective.

The most foundational problem to many liberal economists is the failure to see capitalism as a developing system. Many of the economic models are constructed around the assumption of perfect competition, and this state of perfect competition is static and unchanging. When the economic models do not work in the real world, the conclusion is drawn that there must be some external factor preventing perfect competition, so they advocate for government policies to try and restore it. Yet, they have never once succeeded in this goal.

Originally, Marx was a philosopher with a PhD in philosophy. As a philosopher, he derived the theory of historical materialism, that historical progress— the transition from one economic system to the next — is not driven by human ideals or desires, but is driven by the material world. The development of the material world, which occurs unintentionally of anyone’s will, inevitably forces us to transition from one economic system to the next.

Human societies were based around slave labor for thousands of years. Were humans evil for thousands of years and one day decided to become moral and abolish slave labor? Did we somehow just evolve morality one day, or did one day some genius realize slave labor was wrong because humans somehow missed it all that time? No. That is absurd. Marx argued the abolition of slave-based economic systems was driven by economic factors, which comes back to material foundations of societies, not by ideals. It is a material, not a mental act.

“It is only possible to achieve real liberation in the real world and by employing real means, that slavery cannot be abolished without the steam-engine and the mule and spinning-jenny, serfdom cannot be abolished without improved agriculture, and that, in general, people cannot be liberated as long as they are unable to obtain food and drink, housing and clothing in adequate quality and quantity. ‘Liberation’ is an historical and not a mental act, and it is brought about by historical conditions, the development of industry, commerce, agriculture, the conditions of intercourse.”

— Karl Marx, “The German Ideology”

It is easy to look backwards at prior systems, such as the feudal economic system or the slave economic system, and then figure out how that system developed into the system afterwards. Adam Smith, for example, already explained in detail in his book Wealth of Nations how capitalism developed out of feudalism long before Marx.

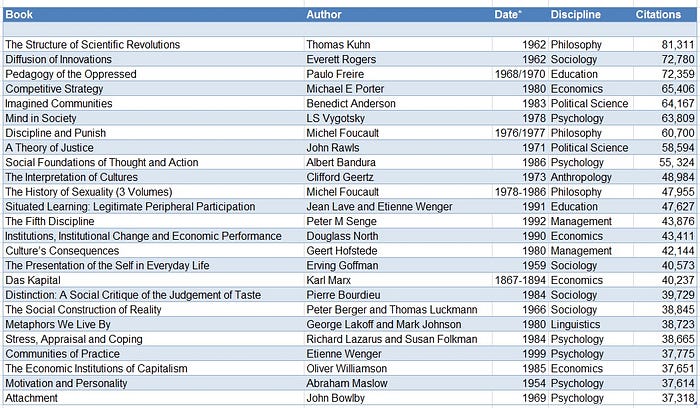

Marx was interested most of all in the more difficult question: “Is capitalism developing, and if so, how? What is it therefore developing into? What would the next system look like?” This is why Marx then became an economist, to try and derive what the future economic system would look like from a rigorous and detailed analysis of capitalism. Marx analyzed the capitalist economic system in his book Capital, which was an incredibly deep analysis to the point where the first of four volumes is about as long as all five books of Wealth of Nations combined. To this day, Capital is the third most cited book in economics of all time, at least according to Google Scholar.

So what did Marx’s analysis reveal? In simple terms, his conclusions were that capitalism, as it develops, inevitably develops towards monopolization. Firms always become larger and larger, the barrier of entry always grows higher and higher, and monopolization always increases more and more over time.

He gives various arguments for this, which he collectively calls “the laws of the centralisation of capitals, or of the attraction of capital by capital,” but the most fundamental is rather trivial to understand. Firms compete with each other by trying to lower their production cost, either to undersell their competition, or to sell at the same price with higher profits. This requires innovation, inventing new machines, new scientific methods, etc.

In the long run, this means the firms with the most capital, or, in other words, the largest firms, are always the victors of any competition. Furthermore, all other firms are forced to then adopt these new machines, or else they will not be able to compete and go bankrupt. This raises the barrier of entry over time, and therefore prevents new businesses from starting up to compete.

“The cheapness of commodities demands, caeteris paribus, on the productiveness of labour, and this again on the scale of production. Therefore, the larger capitals beat the smaller. It will further be remembered that, with the development of the capitalist mode of production, there is an increase in the minimum amount of individual capital necessary to carry on a business under its normal conditions. The smaller capitals, therefore, crowd into spheres of production which Modern Industry has only sporadically or incompletely got hold of. Here competition rages in direct proportion to the number, and in inverse proportion to the magnitudes, of the antagonistic capitals. It always ends in the ruin of many small capitalists, whose capitals partly pass into the hands of their conquerors, partly vanish.”

—Karl Marx, “Capital”

A clear modern example of this would be the smartphone industry. Competition has made cellphone manufacturing more and more complex over time. A cellphone these days is far too complex to be created by a small business. One requires access to enormous factories, machines, and supply chains. According to The Wealth Record, “the net worth of Samsung is pegged at $295 billion.” This is roughly the amount of capital one would need to acquire to even begin to be a serious competitor to Samsung.

The smartphone industry has developed to such a large extent that competition these days is not even intranational but international. There is very little competition between, for example, US smartphone producers, but instead the competition only exists between the US’s single megacorporation (Apple), Korea’s single megacorporation (Samsung), China’s two megacorporations (Huawei and Xiaomi), etc.

“That the small manufacturer cannot survive in a contest whose first condition is production on a continually increasing scale — that is, for which the first prerequisite is to be a large and not a small manufacturer — is self-evident.”

— Karl Marx, “Wage-Labour and Capital”

Marx’s prediction that capitalism would move away from small businesses and perfect competition, towards larger and larger scale oligopolies, and in some sectors true monopolies, started to become apparently true by later economic analysis not long after Marx’s death.

A little over three decades after Marx’s death, Vladimir Lenin — who was banned from political writing at the time — wrote an economic text analyzing the development of capitalism at the time. In it, he gives tons of statistics demonstrating the concentration of capitals. One example, for the United States, I will provide below.

“In another advanced country of modern capitalism, the United States of America, the growth of the concentration of production is still greater. Here statistics single out industry in the narrow sense of the word and classify enterprises according to the value of their annual output. In 1904 large-scale enterprises with an output valued at one million dollars and over, numbered 1,900 (out of 216,180, i.e., 0.9 per cent). These employed 1,400,000 workers (out of 5,500,000, i.e., 25.6 per cent) and the value of their output amounted to $5,600,000,000 (out of $14,800,000,000, i.e., 38 per cent). Five years later, in 1909, the corresponding figures were: 3,060 enterprises (out of 268,491, i.e., 1.1 per cent) employing 2,000,000 workers (out of 6,600,000, i.e., 30.5 per cent) with an output valued at $9,000,000,000 (out of $20,700,000,000, i.e., 43.8 per cent).”

—Vladimir Lenin, “Imperialism, the Highest State of Capitalism”

This phenomenon only continues to be proven true over a century later. The United States today has a far greater concentration of industry than it did during Lenin’s analysis. The small business sector has also consistently been on the decline. This is an observable reality.

Capitalism relies on competition to grow. This is the driving force that leads it to innovate and develop industry. However, as competition rages, it also destroys itself in the process. Therefore, it is impossible not to reach the conclusion that as capitalist economies develop, its growth would only slow down, and the economy would become more and more inefficient the larger and larger it gets.

It is not surprising for Marxists, then, to see that most developed western economies have plummeting productivity growth, and that the European Union’s GDP has not budged an inch in over a decade. In fact, this problem has grown so large that if nothing is done to correct it, the GDP per capita of most developed western capitalist economies may even begin to decline.

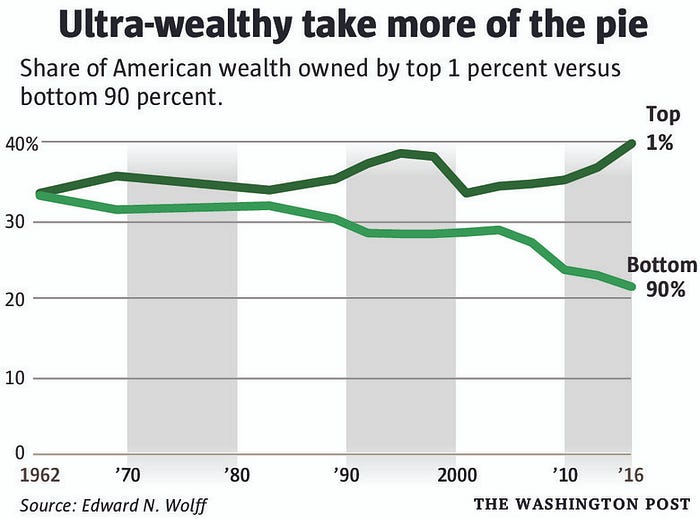

On top of this, a greater concentration of capitals also means a greater concentration of “owners” of that capital, or, in other words, fewer and fewer people who own and control all the wealth in society. This would lead to enormous inequalities in wealth, and sharp divisions between the top and bottom of society.

Rather than an economy where anyone can start a small business, where many people may know the small petty bourgeoisie shop owners personally, rather than the friendly capitalism of earlier days, capitalism instead develops into an incredibly oppressive system dominated by the giant bourgeoisie, distant and alimented from the rest of society.

We see today in the United States, for example, that the top 1% of households own more wealth as the combined 90% of all households.

The problem is even worse when we analyze this globally.

“The world’s 2,153 billionaires have more wealth than the 4.6 billion people who make up 60 percent of the planet’s population, reveals a new report from Oxfam today ahead of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland.”

— Oxfam International, “World’s billionaires have more wealth than 4.6 billion people”

If 4.6 billion is 60% of the world’s population, then the world’s population at the time of the study was around 7.67 billion. This would place the 2,153 as only making up about 0.000028% of the population. That is 0.000028% of the world’s population that controls 60% of the total wealth!

Naturally, Marx believed that the greater capitalism develops, not only would it get more inefficient, but that this would lead to greater social instability. Working people and the capitalists already have opposing interests, but this only would deepen the problem and lead to social instability as a great ever-widening gulf exists between the two.

“If, therefore, the income of the worker increased with the rapid growth of capital, there is at the same time a widening of the social chasm that divides the worker from the capitalist, and increase in the power of capital over labour, a greater dependence of labour upon capital…If capital grows rapidly, wages may rise, but the profit of capital rises disproportionately faster. The material position of the worker has improved, but at the cost of his social position. The social chasm that separates him from the capitalist has widened. “

— Karl Marx, “Wage-Labour and Capital”

Competition gives workers at least some say in what resources are allocated where through their purchasing patterns. Not in a monopolized system. The big bourgeoisie has no reason to listen to the requests of working people, and given workers have less choice in what business to work for, the monopolies also have a greater ability to exploit working people as much as possible. Consider how Amazon today penalizes workers for even using the bathroom. Hence, the greater this concentration of wealth becomes, the greater the social instability, and the struggle between the working class and the wealthy capitalists.

“Then came the concentration of the means of production and of the producers in large workshops and manufactories, their transformation into actual socialized means of production and socialized producers. But the socialized producers and means of production and their products were still treated, after this change, just as they had been before — i.e., as the means of production and the products of individuals. Hitherto, the owner of the instruments of labor had himself appropriated the product, because, as a rule, it was his own product and the assistance of others was the exception. Now, the owner of the instruments of labor always appropriated to himself the product, although it was no longer his product but exclusively the product of the labor of others. Thus, the products now produced socially were not appropriated by those who had actually set in motion the means of production and actually produced the commodities, but by the capitalists. The means of production, and production itself, had become in essence socialized. But they were subjected to a form of appropriation which presupposes the private production of individuals, under which, therefore, every one owns his own product and brings it to market. The mode of production is subjected to this form of appropriation, although it abolishes the conditions upon which the latter rests.

This contradiction, which gives to the new mode of production its capitalistic character, contains the germ of the whole of the social antagonisms of today. The greater the mastery obtained by the new mode of production over all important fields of production and in all manufacturing countries, the more it reduced individual production to an insignificant residuum, the more clearly was brought out the incompatibility of socialized production with capitalistic appropriation.”

— Friedrich Engels, “Socialism: Utopian and Scientific”

This prediction has also been confirmed through various peer-reviewed studies. Wealth inequality is strongly linked to social instability. Furthermore, some recent studies have also shown this social instability reduces financial investments and thus restricts economic growth even further.

“Income inequality, by fuelling social discontent, increases sociopolitical instability. The latter, by creating uncertainty in the politico-economic environment, reduces investment. As a consequence, income inequality and investment are inversely related. Since investment is a primary engine of growth, this paper identifies a channel for an inverse relationship between income inequality and growth.”

— “Income Distribution, Political Instability, and Investment”, European Economic Review

It is not just competition that drives the concentration and centralization of capitals. Marx had shown that the more developed a sector of the economy is, the more it will struggle to have profits. This is a concept I illustrate here. Therefore he had predicted that as capitalism develops, profit rates will have a tendency to decline in the long run.

Marx measured “development” in terms of what he referred to as the “organic composition of capital.” A greater organic composition of capital means that there is a larger proportion of machines to human workers. Humans get more and more replaced by machines over time, and he demonstrates how this leads to falling profits in the long run. You can see this trend by comparing different sectors of the economy, and the ones that are more developed tend to have lower profits.

This falling rate of profits leads to cyclical economic crises. Eventually, as the economy develops, profit rates drop too low that many businesses go bust, causing a wave of bankruptcies and also crashing the banks since many businesses rely on loans which they would be incapable of paying back. This problem gets worse the more capitalism develops because it gets more and more difficult to offset the falling rate of profits.

Here is an easy way to understand the falling profit rates. Each business competes to undercut its competitors. This requires it to adopt ever greater and more complex machines, to increase the scale of its production process. However, the moment a business does this, all others must follow in order to not go bankrupt. The totality of all businesses then adopting this new production process causes the prices to fall, undoing the benefits the original business got from rising prices.

“…the productive forces of labour is increased above all by a greater division of labour and by a more general introduction and constant improvement of machinery. The larger the army of workers among whom the labour is subdivided, the more gigantic the scale upon which machinery is introduced, the more in proportion does the cost of production decrease, the more fruitful is the labour. And so there arises among the capitalists a universal rivalry for the increase of the division of labour and of machinery and for their exploitation upon the greatest possible scale…But the privilege of our capitalist is not of long duration. Other competing capitalists introduce the same machines, the same division of labour, and introduce them upon the same or even upon a greater scale. And finally this introduction becomes so universal that the price…is lowered…below its old…cost of production…Having arrived at the new point, the new cost of production, the battle for supremacy in the market has to be fought out anew. Given more division of labour and more machinery, and there results a greater scale upon which division of labour and machinery are exploited.”

— Karl Marx, “Wage-Labour and Capital”

The benefits are lost, but yet, the capitalist now must purchase an even greater amount of machinery than before. Machines themselves do not produce profits. One can imagine a business as sort of a black box that purchases commodities on the market, applies labor to them, then resells them at a greater value. Purchasing and reselling without any change would not be a profitable endeavor, but mere speculation, which shifts money around. For every successful speculator who bought low and sold high, there must have been one or many brought to ruin who bought high and sold low. Speculation does not create value and could not lead to capitalists, as an entire class taken as a whole, becoming wealthier with time.

Value is created by the labor added to the commodity before it is resold in its new form. By increasing the proportion of machines needed to be maintained in relation to labor, the amount of value added by the laborer becomes ever smaller in proportion to the scale of the machines. This means the rate of profits — the percentage of surplus generated from capital invested — tends to decrease as capitalism develops.

There is one temporary solution to this problem of lower profit rates: consolidation. If your profit rate remains the same, but you expand how much capital you have invested, and also reduce the number of capitalists who you have to distribute profits to, then you have greater absolute profits. Therefore businesses, by consolidating, can still maintain their profits temporarily.

Hence, the falling rate of profit is another reason why capitalism tends to develop towards monopolization in the long run. Every economic crisis tends to be followed by a wave of increased concentration of capital.

This phenomenon was observed independently of Marx, although Marxian economics gives us a way to understand why it occurs. Here is a quote of an observation by an economist made in 1910.

“The cartel movement…instead of being a transitory phenomenon, the cartels have become one of the foundations of economic life. They are winning one field of industry after another, primarily, the raw materials industry. At the beginning of the nineties the cartel system had already acquired-in the organisation of the coke syndicate on the model of which the coal syndicate was later formed — a cartel technique which has hardly been improved on. For the first time the great boom at the close of the nineteenth century and the crisis of 1900–03 occurred entirely — in the mining and iron industries at least — under the aegis of the cartels. And while at that time it appeared to be something novel, now the general public takes it for granted that large spheres of economic life have been, as a general rule, removed from the realm of free competition.”

— Th. Vogelstein, “Die finanzielle Organisation der kapitalistischen Industrie und die Monopolbildungen”

Vladimir Lenin, in the same economic text cited prior, attempted to trace the history of monopolization. He argued that the height of free market competition was in the 1860s, and that the trend of free market competition being replaced by oligopolies, monopolies, and “cartels,” began in the year 1873 with an economic crisis. Monopolization then began to play a major role in the economy following another crash in 1900.

“Thus, the principal stages in the history of monopolies are the following: (1) 1860–70, the highest stage, the apex of development of free competition; monopoly is in the barely discernible, embryonic stage. (2) After the crisis of 1873, a lengthy period of development of cartels; but they are still the exception. They are not yet durable. They are still a transitory phenomenon. (3) The boom at the end of the nineteenth century and the crisis of 1900–03. Cartels become one of the foundations of the whole of economic life.”

— Vladimir Lenin, “Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism”

As we can see, capitalism, as it develops, destroys its own foundations. It relies on competition, but it inevitably develops away from competition as the actual scale of production develops and as the economy continues to advance. Hence, capitalism fundamentally cannot be a permanent economic system.

“The essential conditions for the existence and for the sway of the bourgeois class is the formation and augmentation of capital; the condition for capital is wage-labour. Wage-labour rests exclusively on competition between the labourers. The advance of industry, whose involuntary promoter is the bourgeoisie, replaces the isolation of the labourers, due to competition, by the revolutionary combination, due to association. The development of Modern Industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers.”

— Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, “Manifesto of the Communist Party”

Since capitalism centralizes production and destroys the foundations of competition, Marx viewed that whatever economic system following capitalism must be therefore based in centralized production and economic planning, not in competitive markets.

This system also must resolve the growing contradictions within capitalism, it must resolve this massive wealth inequality, social instability, and economic stagnation. For all prior transitions from one economic system to the next, this was done through a change in property relations. Therefore, too, Marx viewed the transition from capitalism to the next system to also require a change in property relations.

The conclusion, therefore, was that the next economic system would be based in public ownership of the means of production, operating according to a central plan.

“What will this new social order have to be like? Above all, it will have to take the control of industry and of all branches of production out of the hands of mutually competing individuals, and instead institute a system in which all these branches of production are operated by society as a whole — that is, for the common account, according to a common plan, and with the participation of all members of society. It will, in other words, abolish competition and replace it with association.”

— Friedrich Engels, “The Principles of Communism”

Making these large-scale monopolies public property, democratically controlled, and accountable to the public at large, solves all your problems. Wealth no longer accumulates in a tiny amount of hands but instead in the public at large, eliminating the social instability and increasing the living standards of regular people. The wealth can also be invested back into production, stimulating economic growth and getting around the problem of a stagnant economy, what Chinese economists call “liberating the productive forces.”

Hence, we see now why socialist countries attempt a transition towards public ownership. Simply pulling a table from List of countries by public sector size on Wikipedia, we can see a list of the sizes of various countries by public sector — as in, the percentage of workers who work in the public sector — according to the International Labour Organization. Two of the top three countries are socialist and Marxist according to their constitutions. Belarus used to be part of the Soviet Union, and Lukashenko has constructed a market socialist economy there (Source: “The Market-Socialist Country”, Problems of Economic Transition).

We also understand, then, why many of these countries still have a private sector. The demand for public property does not come out of simply believing this is more moral or ideal. It is a response to economic conditions. Yet, not all sectors of the market develop at equal rates, so Marx expected that the transition from capitalism to communism would be gradual, with the gradual expropriation of private property alongside a rapidly developing economy.

The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.

— Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, “Manifesto of the Communist Party”

Will it be possible for private property to be abolished at one stroke? No, no more than existing forces of production can at one stroke be multiplied to the extent necessary for the creation of a communal society. In all probability, the proletarian revolution will transform existing society gradually and will be able to abolish private property only when the means of production are available in sufficient quantity.

— Friedrich Engels, “The Principles of Communism”

The large amount of nationalization in China, for example, has allowed its economy to become incredibly efficient. Monopolies no longer act as a hindrance but instead act as the very engine of its economic growth. Take a look at China’s high speed rail, for example. Liberal economics would tell you that monopolies are inherently inefficient. Yet, the state in China not only has a monopoly on high speed rail, but it has also laid more kilometers of high speed rail than the entire rest of the world combined.

“China has put into operation over 25,000 kilometers of dedicated high-speed railway (HSR) lines since 2008, far more than the total high-speed lines operating in the rest of the world.”

China’s Experience with High Speed Rail Offers Lessons for Other Countries

Far from inefficient, the public monopolies are in fact far more efficient than anything else in the rest of the western world. Monopolies are inevitable whether we like them or not. Public monopolies are far superior to private ones. The gradual transition from private to public ownership is the only way to maintain long-term growth and social stability.