Often I am asked, “why did Marxism-Leninism fail to bring the workers’ paradise into existence?” Sometimes people respond to this by pointing to the democratic benefits Marxist-Leninist countries have provided. However, we would be fooling ourselves to pretend any Marxist-Leninist country created anything coming close to a “workers’ paradise.” That’s not to say there were not huge gains for workers, don’t get me wrong, but criticism of the inadequacies of workers’ democracy in these countries should be taken seriously and responded to honestly.

What I want to discuss is why. However, I’m probably going to approach this question from a way you might not expect. I’m not going to criticize failures of specific leaders, or criticize people for not being “true Marxists.” I do believe that many Marxist-Leninists revolutionaries did indeed want to create as democratic society as possible, with as much worker control as possible.

The point is this. Creating democracy is not about finding the right formula. It is not about finding the right recipe. Many believe if the Soviets just implemented their recipe for democracy, it would have worked out perfectly.

To these people, the problem ultimately comes down to “bad ideas.” They usually pin the blame on Stalin, Lenin, Mao, etc, for having “bad ideas.” If only they had better thoughts, then the genuine workers’ paradise would’ve been possible.

I recall a book by the name of Marx’s Capital: Illustrated which has this same point of view. It presents the democratic failures of many Marxist-Leninist countries as purely a result of bad leaders with bad ideas, and paints people like Stalin and Castro as “not true Marxists.”

Obviously the message here is simple: “There was lacking worker control in the Soviet Union because of Stalin. If only they listened to Rosa Luxemburg then there would have been a workers’ paradise!”

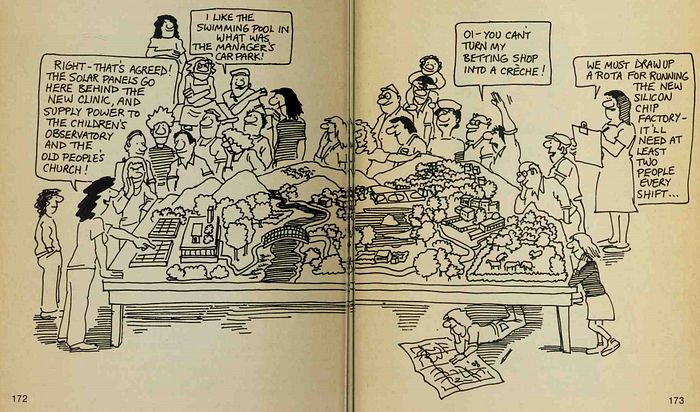

I do not exaggerate when I say “workers’ paradise.” This book depicts what it views “true socialism” to be, and it depicts it as workers all standing around a table chatting and happy with smiles on their faces.

The image this book is depicting is the “true workers’ paradise that could’ve been achieved if it wasn’t for that dastardly Stalin not listening to Luxemburg!!”

But, I have a different idea.

Maybe the failure of implementing this kind of utopian society has nothing to do with anyone's ideas. Because everyone failed. Universally. This is not just Marxist-Leninists, but no revolution anywhere has succeeded in creating anything close to a workers’ paradise.

Maybe it has simply nothing to do with a lack of proper recipe.

Maybe it is something a bit deeper.

A Materialist Conception of Democracy

A Discussion On Slavery

For thousands of years, human societies were largely slave-based. Most people were slaves, the economy was largely driven by slave-labor, such as in ancient Egypt or ancient Rome. At some point, humanity started to move beyond slavery. It wasn’t immediate abolish, but quite gradual. The feudal system still maintained some level of slavery, but overwhelmingly replaced slaves with peasants.

Why did human societies base itself off of slavery for so long? Why did humanity start moving away from slavery? Was it because humans were evil for thousands of years and one day evolved “goodness?” Was it because some super genius one day discovered through his great intellect that slavery was, indeed, bad?

No, that would be ridiculous.

The reason humanity moved beyond slavery was not due to any sudden discovery of “goodness.” Rather, it was simply due to economic factors.

Slaves are in fact quite inefficient producers. They do not own anything they produce, so their motivation is inherently to consume as much as possible and to work as little as possible. Only threats of pain can drive a slave to continue to work. But this not only has its limitation, but also requires a large infrastructure of those to deliver this pain. Slaves require a slave driver, or in other words, a retainer.

The slave can’t die, either. The slave master, the proprietor of the land, has to keep the slave alive in order for production to continue. Unlike the peasant who provides for himself, the slave has to be clothed, fed, housed, potentially educated, etc, all at the proprietor’s expense.

In another words, slave workers have low productivity, high maintenance costs, and requires more managerial oversight.

Furthermore, these problems get more and more compounded the more complex production becomes. The more complex machines the slave has to operate, the more education he has to receive. The more complex the production process, the more and more slaves are required, and thus the greater the cost of managerial oversight.

In order for the scale of production to continually increase, eventually you need many layers of organization. You need managers over managers, and workers on multiple levels. For the slave system, this would mean retainers of retainers and enslaved retainers. Many slaves would be forced to work by a retainer, while also being forced to force those subordinate to them to work.

In other words, you would have layers upon layers of slaves forcing other slaves to work. This system is clearly unsustainable. Slavery on practice almost rarely could achieve more than a single layer. The slaves on farms had retainers, but those retainers did not have retainers.

Not only would there be increasing unsustainable due to a potential revolt as this system added more and more layers, but the cost would also skyrocket of the immense amount of retainers and tools to enforce punishment and inflict pain. The slave system was in no way compatible with anything beyond very primitive labor, beyond anything that required limited education or organization.

When agriculture became improved enough to start producing a surplus, this surplus could then be traded as it was no longer necessary. Initially, this surplus had nowhere to go. The inefficiency of slavery was no problem, because the great barons already had far too much surplus than they needed, and would often even throw great feasts to give it away freely.

However, with the development of trade cities, there became a new use for surplus. The proprietors could sell the surplus to the cities in exchange for manufactured goods. The proprietor selling off this surplus meant there was less surplus left over to pay for the inefficiencies of slavery. He could no longer afford to feed and clothe the slave, he could no longer afford to pay the retainers to control the slaves.

In other words, the newfound ability to grow their wealth through market exchanges did not initially have the effect of growing their power and influence, but quite the opposite. The barons relinquished control over slaves more and more in order to have more surplus to exchange with the rising cities.

The proprietors would, in the beginning, spend all their wealth in one place, and that place being directly on their slaves, providing them everything for their slaves, and thus giving them incredible power and influence over the slaves.

However, when he exchanges his goods on a market, he is paying for the labor of someone far outside of his domain, while reducing what he provides within his domain. This spreads out the influence of his wealth all over the globe, and thus reduces his control and influence over those directly within his domain.

The tenants having in this manner become independent, and the retainers being dismissed, the great proprietors were no longer capable of interrupting the regular execution of justice or of disturbing the peace of the country. Having sold their birthright, not like Esau for a mess of pottage in time of hunger and necessity, but in the wantonness of plenty, for trinkets and baubles, fitter to be the playthings of children than the serious pursuits of men, they became as insignificant as any substantial burgher or tradesman in a city. A regular government was established in the country as well as in the city, nobody having sufficient power to disturb its operations in the one any more than in the other.

— Adam Smith, “The Wealth of Nations”

This inability to control the slaves, however, turned out not to be economically devastating to the proprietors. By dismissing the retainers and allowing for a level of autonomy, peasant laborers actually became more economically productive than the slaves. The peasant could keep what he produced in excess, and thus was motivated to work hard.

It also had the effect of reducing the power and influence of the great barons, thereby allowing for the expansion of this market economy throughout the countryside, which was historically wrought with war and violence through constant conflicts between the great barons. This slowly paved the way for capitalism, which only continually increased the wealth of the proprietor.

In other words, economic factors drove the proprietors to begin giving up slavery. Not anyone’s ideas. The idea for the abolition of slavery only began to materialize long after much of the economy had moved beyond slavery, as abolishing slavery prior not only lacked a real mechanism to do so — as it would be impossible to enforce in a system of feudal anarchy where not even the king had full control over his own realm — but it also would be economically unfeasible, as it was the basis of the entire economy.

The idea to abolish slavery did not materialize until long after it had already been abolished throughout most of the economy, and laws to abolish slavery mainly stomped out small sectors of the economy where slavery still had yet to die out.

The Economics of Democracy

Democracies are not simply something that exist in our heads. We argue over ideas all the time. We argue over what Marxist had the best ideas. We argue over what Marxist — if only they were leading the revolution — would’ve created the best society.

However, democracies are not ideas. They are physical things that exist in the real, physical world. You have real people who participate in real ways in a real system existing in the real world. These ideas might sound amazing in your head, but eventually they have to leave your head and manifest themselves into the real world.

Modern day bourgeois democracies did not come into existence merely due to people having good ideas on how to establish them. The dissolution of slavery occurred due to economic factors. It occurred due a change in the material base of society. Bourgeois democracy did not develop either until capitalism had further developed out of the feudal system, laying material base necessary for the establishment of the system.

The kind of democracy Marxists call for extends even further than this. Marxists wish to see democracy not simply in the government, but through all spheres of life. They want worker control over the means of production, worker control over production and distribution. Marxists want economic democracy.

For the economy to be controlled democratically, this requires it to be controlled with intention. In other words, this requires it to be planned. Workers would not simply be reacting to forces outside of their control in a fit of survival in the chaotic anarchy of the markets, but would instead, through direct control, plan the entire economy meticulously and intentionally in their own interests.

The increase in the productive forces gives humanity more and more control over the natural world and their own social structure. Without an understanding of electricity, humanity can only react to it. However, with the development of electronics, humanity has learned how electricity behaves and has developed the technology to control it.

Humanity does not simply react to natural laws, however, but also the laws of its own social structure. Neither a worker nor an employer has control over the laws of supply and demand. He can only react to them and hope to survive in the anarchy of the markets.

On the threshold of human history stands the discovery that mechanical motion can be transformed into heat: the production of fire by friction; at the close of the development so far gone through stands the discovery that heat can be transformed into mechanical motion: the steam-engine. — And, in spite of the gigantic liberating revolution in the social world which the steam-engine is carrying through, and which is not yet half completed, it is beyond all doubt that the generation of fire by friction has had an even greater effect on the liberation of mankind. For the generation of fire by friction gave man for the first time control over one of the forces of nature, and thereby separated him for ever from the animal kingdom.

— Friedrich Engels, Anti-Durhing

The development of the markets necessitates the constant strive for innovation. This strive for innovation leads to development of new technology, new infrastructure, and thus drives humanity towards conquering the laws of nature in ever more sophisticated ways, as industry continually develops.

However, the laws of nature are not the only things which humanity continually conquers with the development of industry. Industry does not merely develop, but necessarily development on an ever increasing scale.

It is evident that the small manufacturer cannot survive in a struggle in which the first condition of success is production upon an ever greater scale. It is evident that the small manufacturers and thereby increasing the number of candidates for the proletariat — all this requires no further elucidation.

— Karl Marx, “Wage Labor and Capital”

The constant increase in the scale of production necessitates new technology and infrastructure to socialize the laborers. It necessitates more and more laborers being brought out of competition with one another, and into cooperation under a single, large-scale business. It continually transforms isolated laborers into socialized laborers on an ever increasing scale.

In the medieval stage of evolution of the production of commodities, the question as to the owner of the product of labor could not arise. The individual producer, as a rule, had, from raw material belonging to himself, and generally his own handiwork, produced it with his own tools, by the labor of his own hands or of his family. There was no need for him to appropriate the new product. It belonged wholly to him, as a matter of course…Then came the concentration of the means of production and of the producers in large workshops and manufactories, their transformation into actual socialized means of production and socialized producers.

— Friedrich Engels, “Socialism: Utopian and Scientific”

This process of the socialization of labor has only continually increased year after year. Competitive markets become transformed into monopolies. That which was originally driven by the laws of supply and demand is not controlled intentionally, through an organized plan, carried out by a socialized institution of laborers working in cooperation with one another.

Competition becomes transformed into monopoly…This is something quite different from the old free competition between manufacturers, scattered and out of touch with one another, and producing for an unknown market…Capitalism…leads directly to the most comprehensive socialisation of production; it, so to speak, drags the capitalists, against their will and consciousness, into some sort of a new social order, a transitional one from complete free competition to complete socialisation.

— Vladimir Lenin, “Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism”

The ability to intentionally plan the economy not only requires real infrastructure and technology, but this technology is necessarily laid by the development of capitalism itself. Capitalism is always in the process of developing away from competition and towards economic planning.

It is not merely voting that is necessary for workers to truly be in charge in production. It does not matter how many votes are cast if the infrastructure simply does not exist to transform those inputs into outputs. If there is no infrastructure for actually developing the economy, all these votes will never lead to the democratic will of the voter actually being expressed.

Utopians believe that the problem is always lack of direct democracy. More and more direct democracy is always their solution. More and more voting. Voting is insufficient here. Without the tools to actually carry out economic plans, these votes will be for naught. The economy will never reflect the will of the workers.

Abolition of private property does not simply mean private property is decreed out of existence. It means that the anarchy of the markets is replaced by intentional planning. It is planning which separates the workers subjected to market forces outside of their control, to real agents of power, who themselves deliberately decide production and distribution.

The abolition of private property is therefore the abolition of the anarchy of production, and the ascent of the working class from mere agents driven by a social structure outside of their control, to the genuine creators of their own history.

With the seizing of the means of production by society, production of commodities is done away with, and, simultaneously, the mastery of the product over the producer. Anarchy in social production is replaced by systematic, definite organization. The struggle for individual existence disappears. Then, for the first time, man, in a certain sense, is finally marked off from the rest of the animal kingdom, and emerges from mere animal conditions of existence into really human ones. The whole sphere of the conditions of life which environ man, and which have hitherto ruled man, now comes under the dominion and control of man, who for the first time becomes the real, conscious lord of nature, because he has now become master of his own social organization. The laws of his own social action, hitherto standing face-to-face with man as laws of Nature foreign to, and dominating him, will then be used with full understanding, and so mastered by him. Man’s own social organization, hitherto confronting him as a necessity imposed by Nature and history, now becomes the result of his own free action. The extraneous objective forces that have, hitherto, governed history,pass under the control of man himself. Only from that time will man himself, more and more consciously, make his own history — only from that time will the social causes set in movement by him have, in the main and in a constantly growing measure, the results intended by him. It is the ascent of man from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom.

— Friedrich Engels, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific

Confronting Reality

The harsh truth which utopians do not wish to discuss is that this level of worker agency inherently requires the material infrastructure to carry out these economic plans. If an economy lacks the infrastructure to carry out efficient plans, it will be fundamentally impossible to truly place the working class in the saddle.

The “ideas” do not matter here. Neither Leon Trotsky nor Rosa Luxemburg would not have established the workers’ paradise. The problem here is necessarily material. The Soviet Union attempted to establish economic planning largely by fiat despite its incredible levels of underdevelopment.

This necessarily meant that its ability to transform democratic input from workers into economic output was necessarily limited. In other words, it lacked the material base necessary to establish an efficient fully planned economy, and therefore lacked the material base to fully establish worker democracy.

The USSR was still rather poor in the 1930s when they decided it would be a good time to switch to a fully planned economy. The infrastructure to carry this out was hardly there, and they even gave up expropriating the agricultural sector because it was so underdeveloped it was simply impossible.

The incredibly limited infrastructure meant that the system had very rudimentary and primitive ways of responding to changing preferences in the population. On top of this, the Soviet Union failed to adequately improve its planning techniques. In the 1980s, computer had already become a thing and were being used in many American businesses, but the Soviet system was very difficult to overhaul, meaning they were planning one of the largest economies in the world still largely by hand, which in and of itself is an incredibly impressive feat, but it also became rather inefficient.

Heavy industry is pretty simple, light industry is pretty complicated. The Soviet Union excelled at heavy industry, but after it had managed to meet people’s basic needs and provide the basics like health care, education, and housing, people started to demand more variety in consumer products.

Yet, the Soviet Union fundamentally could not match the complexity of western market economies in its ability to provide consumer products in a great variety. It had grown to the largest economy in the world while still largely planning everything by hand, and the planning technology and infrastructure was lagging far behind.

You can’t solve this problem by just having “more democracy”. It’s a problem of information. The economy was too enormous and complex to actually gather all that information and then respond to consumer demand. The USSR had tons of places for workers to have democratic input, but it did not matter. As its clunky system aged, it continually lacked the ability to efficiently transform any sort of democratic input into economic output.

By the Soviet government extending itself far beyond what it could reasonably plan, it inevitably created the lack of democratic control. And late in the Soviet Union, this problem only got worse and worse as people demanded more complex things, more and more variety in consumer goods, which were a lot more complex to provide than basic necessities, and people started to become dissatisfied with the system.

The Soviet Union is they never found a way to really solve this crisis because they had a lot of bigger issues brewing as well. Issues such as corruption, regional nationalism, and incompetency in the leadership lead to a failure for any adequate solution to be found.

The Rise of “Revisionism”

The basis of socialism is planning, and as we have established, planning develops more and more over time as a result of the development of the markets, as this process of industrialization socializes labor as it continually increases the scale of production. Socialism necessitates this big industry for its in order to have any semblance of competent economic planning.

Big industry is not something that can be instituted by fiat, either. As the inefficient economic planning will necessarily lead to inefficient economic development. Attempting to abolish private property in an underdeveloped economy dominated by small producers would be economically impossible and inevitably lead to disaster in the long-run.

What is to be done? One way is to try to prohibit entirely, to put the lock on all development of private, non-state exchange, i.e., trade, i.e., capitalism, which is inevitable with millions of small producers. But such a policy would be foolish and suicidal for the party that tried to apply it. It would be foolish because it is economically impossible. It would be suicidal because the party that tried to apply it would meet with inevitable disaster. Let us admit it: some Communists have sinned “in thought, word and deed” by adopting just such a policy. We shall try to rectify these mistakes, and this must be done without fail, otherwise things will come to a very sorry state.

— Vladimir Lenin, “The Tax in Kind”

Underdevelopment implies a very low barrier of entry for businesses. Any underdeveloped sector of the economy will not be dominated by big industry, and thus small industry could reasonably compete on the market. A small barrier of entry makes it possible for small producers to spontaneously enter the market, as many people will have the necessary funds.

Both the inefficiencies in government planning and the spontaneity of small producers to enter a market are a reflection of underdeveloped. These also contradict. The small producers would not be legal, and would thus have to forcibly dispersed by the inefficient government. The inefficient government would thereby have to constantly disperse the producers who only appear to make up for the government’s own inefficiencies, this dispersal thereby destroying its own economy in the process.

This is why Lenin discouraged the dispersal of small producers and instead encouraged to allow their development. The dispersal of the small producers not only harms your own economy, but requires additional wasted funds for bureaucratic oversight. Lenin instead encouraged encouraging market development in order to lay the foundations for socialized production.

Capitalism is a bane compared with socialism. Capitalism is a boon compared with medievalism, small production, and the evils of bureaucracy which spring from the dispersal of the small producers. Inasmuch as we are as yet unable to pass directly from small production to socialism, some capitalism is inevitable as the elemental product of small production and exchange; so that we must utilise capitalism (particularly by directing it into the channels of state capitalism) as the intermediary link between small production and socialism, as a means, a path, and a method of increasing the productive forces..

— Vladimir Lenin, “The Tax in Kind”

Hence, Lenin’s inevitable conclusion is the lack of big industry necessitates the utilization of market forces. There is no other way. Underdevelopment necessarily requires markets, because markets are the only system that can efficiently lay the foundations for big industry.

Free competition is necessary for the establishment of big industry, because it is the only condition of society in which big industry can make its way.

— Friedrich Engels, “The Principles of Communism”

The utopians demand the abolition of private property by fiat, and the establishment of full economic planning by fiat. Yet, socialism requires economic planning, economic planning requires big industry, and big industry can only be developed through market competition.

The only necessary conclusion is that private property simply cannot be abolished by fiat. It must continue to exist in every sector of the economy as long as that sector has yet to socialize on its own.

In other words, you cannot abolish private property in one stroke because various sectors of the economy would be underdeveloped and thereby lacking the necessary productive forces. The transformation of capitalism into socialism must necessarily be a gradual process inline with gradual economic development, and complete abolition of private property would only be possible with incredibly, incredibly high levels of economic development.

Will it be possible for private property to be abolished at one stroke? No, no more than existing forces of production can at one stroke be multiplied to the extent necessary for the creation of a communal society. In all probability, the proletarian revolution will transform existing society gradually and will be able to abolish private property only when the means of production are available in sufficient quantity.

— Friedrich Engels, “The Principles of Communism”

So what, then, is the role of the communist party? Simply put, the role of the communist party is to not only gradually transform society by degree, but to also hasten this process, to speed up the development of the productive forces.

The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.

— Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, “Manifesto of the Communist Party”

Hence, the failures of the Soviet model lead to those who criticized the very notion of attempting to establish economic planning in all spheres of life which have yet to develop big industry through market mechanisms.

The necessary conclusion is, then, that market mechanisms and private property must necessarily be restored in the inefficient areas of the economy. While this is often described as “revisionism”, it is, in fact, far more accurate to a classical understanding of Marxism.

Conclusion

Slavery was not abolished through great “ideas.” Neither will some “workers’ paradise” be established simply through great “ideas.” The failure of the Soviet Union to achieve any sort of worker utopia cannot simply be resolved by “more direct democracy.” Nor could it be resolved through simply replacing Stalin with Rosa Luxemburg or Trotsky.

Establishing worker control of the economy requires the ability to transform democratic input into economic output. This requires vast amounts of material infrastructure and technology and is not simply something you can decree into existence by fiat, but is something you must build.

Full worker control will not be established without material development. Instituting full economic planning by fiat is impossible. It will only establish an inefficient form of planning that will fail to actually adequately plan the economy, thereby failing to actually represent the demands working people, thereby failing to truly place working people in the saddle.

The truth is, democracy itself is driven by economic development, by the progress of history. It was economic development that took humankind outside of primitive hunter-gatherer tribes and established the first civilizations. It was economic development that led to the abolition of slavery. It was economic development that abolished the feudal system.

Economic democracy implies that the will of the workers is directing, planning, the economy. Economic planning inherently requires large-scale infrastructure. Large-scale infrastructure cannot be decreed into existence, but can only come into existence efficiently through market mechanisms.

Marxists should drop the obsession of implementing some “workers’ utopia”. Marxists should drop the obsession of restoring some glorified 20th century past. Marxists should focus on actually moving humanity towards socialism. This can only occur through the progress of history. Through economic development. Through rapidly developing the productive forces.

The idealist notion analysis of democratization should be abandoned for a materialist one.

It is only possible to achieve real liberation in the real world and by employing real means, that slavery cannot be abolished without the steam-engine and the mule and spinning-jenny, serfdom cannot be abolished without improved agriculture, and that, in general, people cannot be liberated as long as they are unable to obtain food and drink, housing and clothing in adequate quality and quantity. “Liberation” is an historical and not a mental act, and it is brought about by historical conditions, the development of industry, commerce, agriculture, the conditions of intercourse.

— Marx, The German Ideology