I explained in this post here how to calculate value. Prices, however, are not the same as value, which is something I also explain here. Why? Because supply and demand also affect prices, and value is simply the equilibrium point of supply and demand.

“At the moment when supply and demand equilibrate each other, and therefore cease to act, the market price of a commodity coincides with its real value, with the standard price round which its market prices oscillate.”

— Karl Marx, “Value, Price, and Profit”

Surely a fully planned economy would still have a supply of goods and services. Surely a fully planned economy would still have a demand in proportion to those goods and services. The reasonable conclusion here is that supply and demand must also play a role in a planned economy, even a fully planned one without any markets, and therefore prices and value must deviate somewhat.

There are two ways of distributing resources within a planned economy. The first is out of a set public fund. Things like health care, for example, are paid for from the public fund. Health care is something everyone needs, and is free at the point of service. It therefore, even in a fully planned economy, would be funded in a similar way to taxation, by simply paying for it out of slightly reducing the pay of everyone in society.

This works well for things everyone needs, but not so much for consumer goods. Everyone’s preferences are different, and it’s difficult to plan consumer goods just right. Rather, most heavily planned economies used a public store where all the goods are laid out for you to pick your preferences, and then you pay for them with “money” you received from your work. In a system like this, the effect of supply and demand become quite apparent.

Think of it like this, for example. What if the state is producing cars at a rate of 12,000 per year, and half-way through the year, they find that 8,000 cars have been purchased? The rate cars are being produced cannot keep up with this. The demand is greater than the supply, and there will be a shortage.

The shortage could be offset by raising the price somewhat. Remember, demand does not refer to how many people want something. It refers to how many people are willing to buy something at a given price. Increasing the price will decrease the demand for it, avoiding the shortage.

Of course, the reason there is a shortage is because more people want something than is being produced. This can serve as a signal to scale up production, in a very similar way that in a capitalist economy, if an industry all of the sudden becomes more profitable, then other investors may flow into it.

On the flip-side, if no one is buying the good or service so you have to drop the cost in order to increase demand for it, then this signals that too much is being produced and production needs to be scaled down, in a similar sense that if a good or service becomes unprofitable in a capitalist economy, then many businesses will pull out and stop producing it.

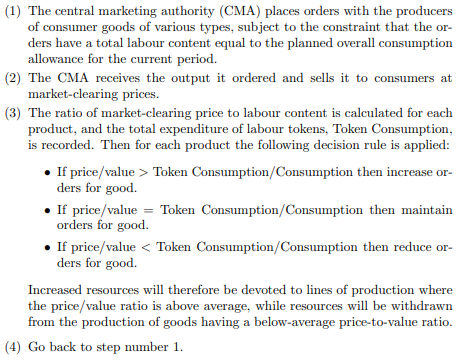

Below is a summary of this algorithm.

In order for this algorithm to be useful, value still must be calculated. If value is not calculated, then what is a large or small price will be arbitrary. By calculating value, price ceases to be arbitrary and becomes tied in directly to production costs. Prices can then be adjusted according to purchasing habits in order to prevent shortages and surpluses, and this will also allow for feedback into production automatically similar to how it functions within a capitalist economy.

These prices are referred to here as market-clearing as they are adjusted away from their value with the purpose of clearing the market’s shelves in the most efficient way. If the price is too low, the shelves will clear too quickly causing a shortage. If the prices are too high, the shelves will not clear at all. The market-clearing price is value adjusted for supply and demand.

The price may have to be adjusted many times throughout the year. If economic plans only change from year-to-year, then the average can be taken from the changes in price throughout the year.

The value of a commodity can still be expressed, even in a planned economy, in terms of c + v + s. Workers are not able to get paid the full value of their labor, as some surplus will necessarily be needed to be reserved for the public find, for things like health care and the expansion of industry. The difference here is that s no longer represents profits, but a general “taxation” on the purchase of every commodity, and v no longer represents the value of labor power. The value c would no longer represent purchases from the market, but rather, the output of one industry allocated to another, things like machines, buildings, tools, etc. In other words, “dead labor,” as Marx put it.

If we define L = v + s, then this can be rewritten as c + L where L represents the value added to the good or service based on labor inputs. Let’s say, for example, in some industry, c = 6000; L = 2000; c + L = 8000. Let’s also say that value here is measured in hours. This would tell us that in this given industry, 6000 labor hours worth of dead labor plus 200 hours of labor gives us an output valued at 8000 hours of labor. If this industry is car manufacturing, for example, then a single car would be valued — and thus initially priced at — 8000 labor hours.

The ratios c/(c + L)= 0.75 and L/(c + L)= 0.25 are interesting here. We will refer to these as the dead labor ratio and the labor added ratio form here on out. These ratios can give us an idea how much we need to scale up or down production. If we increase the number of workers, we will likely need to increase the number of dead labor inputs s well. If we increase the number of dead labor inputs, we will also likely need to increase the number of workers. If you add new machines, but there are no new laborers to use those machines, then they are useless.

Let’s say, back to our car analogy, we plan to produce 12,000 cars per year, and half-way through the year, we find that 8,000 cars are being purchased. Here, the initial price, equal to value, is too low, and we have to bump it up throughout the year to prevent a shortage. The next question we need to ask is how many cars would they have purchased if we did not change the price? Since they had purchased 8,000 in six months, we could predict that they would have purchased 16,000 in twelve months. Our price had to go up to prevent a shortage of 4,000 cars.

Each car has a value of 8,000. If we multiply this car deficit by the value, we find a shortage of 32,000,000 labor hours. We can’t just allocate more hands to car production, because allocating more hands inherently means allocating more machinery. This is where the dead labor and labor added ratios come in handy.

If we multiply this deficit in labor hours by the dead labor ratio, 0.75, we get 24,000,000. If we multiply this deficit in labor hours by the labor added ratio, 0.25, we get 8,000,000. This tells us that we need to scale up car production by increasing the flow of raw materials to it by a value of 24,000,000 and increasing the human labor inputs 8,000,000.

This would give us a starting point to understand how production needs to change. Of course, there are several things to note here. First, not all industries may scale so linearly. This would still give us, more or less, a decent starting point. Second, if we increase dead labor inputs, this means we have to increase the outputs for other industries. This would require us to rewrite the plan for pretty much the entire economy. There are algorithms for allocating resourcing efficiently, which I may go into in the future, but every year these algorithms would need to be rerun to ensure that these changes can go all the way down the supply chain.

The point here is to show that simple consumer buying habits, even within a fully planned economy, can be fed back into production in order to make adjustments, without ever even having to ask the consumer. There are, of course, limitations to this, and it would not replace more direct methods, such as surveying the population, elections, accountability meetings, etc, which all give direct inputs into planning from the population. But this indirect method would serve as a supplement to these things and help to avoid shortages and surpluses.