“If someone bakes a mud pie, it must have value.”

Value is not simply labor time, but socially necessary labor time. Value is a social construct related to but not the same as market price. The market price of a hamburger differs in the US and in China. What is the market price of a hamburger on a deserted island? The question makes no sense, as there is no market. Value is a social function, it requires a society, and it differs from society to society.

“As the exchangeable values of commodities are only social functions of those things, and have nothing at all to do with the natural qualities, we must first ask: What is the common social substance of all commodities? It is labour. To produce a commodity a certain amount of labour must be bestowed upon it, or worked up in it. And I say not only labour, but social labour. A man who produces an article for his own immediate use, to consume it himself, creates a product, but not a commodity. As a self-sustaining producer he has nothing to do with society. But to produce a commodity, a man must not only produce an article satisfying some social want, but his labour itself must form part and parcel of the total sum of labour expended by society. It must be subordinate to the division of labour within society. It is nothing without the other divisions of labour, and on its part is required to integrate them.”

— Karl Marx, “Value, Price, and Profit”

Since value is a social function, in order for labor to actually add value to a commodity, it must be labor that fulfills a social function. In order words, the labor must produce something that serves a social utility. If you work to produce something that is useless to society, then it will hold no social utility, and therefore the labor will not count as social labor, and will add no value to the commodity.

“…nothing can have value, without being an object of utility. If the thing is useless, so is the labour contained in it; the labour does not count as labour, and therefore creates no value.”

— Karl Marx, “Capital”

“If Labor Must Produce Something of Social Utility to Have a Value, that Proves Utility Determines Value, not Labor.”

Often I hear the argument that Marx “contradicted” himself by arguing that something needs a social utility first before it can take on a value, and therefore Marx is “admitting” that utility determines value, since without utility, something will have no value.

Let me give an analogy.

Let’s say I want to go on a road trip. If I go on the road trip, I will burn a certain amount of gasoline. If I do not go on the road trip, I will burn no gasoline. Therefore, my desire to go on the road trip will determine whether or not I will burn gasoline.

From this, does it logically follow that the amount of my desire therefore determines exactly how much gasoline I would burn? In other words, can you predict, with no other information than the amount I desire to go on a road trip, the exact number of gallons of gasoline I would burn on that trip?

Obviously not. You would need to know the length of the trip, the efficiency of my car, the traffic at the time, etc. Even though having a desire or not having a desire determines whether or not I will burn gasoline at all, it does not then logically follow that knowing how much I desire to go on that road trip can then predict the exact amount of gasoline I would burn.

In the same sense, yes, having a social utility or not does determine whether or not something can have a market price at all. But it does not then logically follow that the market price it takes on is solely determined by the amount of utility.

Markets do not exist in people’s heads. They exist in the real world. When you go to implement social utility in the real world, you quickly run into certain limitations from that real world, and so you also need information on the real world to make any sort of price predictions, not solely what is in people’s heads.

You need to know other variables, such as the actual cost it takes to produce something, which sets an absolute minimum on how much the business can sell it for, and the amount of market competition in that economy, which sets a maximum on how much that business can get away with selling their product for.

“If someone takes longer to produce something because they are lazy, it must cost more.”

No matter what cost goes into producing something, producers all bring to the same market. If I go to the store and there are two commodities qualitatively identical, let’s say, two identical apples, but they cost different, I’m going to buy the cheaper one. Everyone would. This would force the person overpricing the apples to drop the price. The consumer does not care about the cost that went into producing it, only the price, and since all commodities are brought to the same market, they all have to be priced the same.

“The cattle bred upon the most uncultivated moors, when brought to the same market, are, in proportion to their weight or goodness, sold at the same price as those which are reared upon the most improved land.”

— Adam Smith, “The Wealth of Nations”

This, again, goes back to value being a social construct. Value is not simply labor time but socially necessary labor time. If, for example, I get lucky and find some gold underneath my house, it required very little labor for me to find that gold. However, that doesn’t mean the gold will be worthless. In the society I live in, gold requires a lot of labor to mine and refine, so it will still be worth the social average. The only way for the value of gold to decline is if the social average goes down for all of society.

“Some people might think that if the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of labour spent on it, the more idle and unskilful the labourer, the more valuable would his commodity be, because more time would be required in its production. The labour, however, that forms the substance of value, is homogeneous human labour, expenditure of one uniform labour power. The total labour power of society, which is embodied in the sum total of the values of all commodities produced by that society, counts here as one homogeneous mass of human labour power, composed though it be of innumerable individual units. Each of these units is the same as any other, so far as it has the character of the average labour power of society, and takes effect as such; that is, so far as it requires for producing a commodity, no more time than is needed on an average, no more than is socially necessary. The labour time socially necessary is that required to produce an article under the normal conditions of production, and with the average degree of skill and intensity prevalent at the time.”

— Karl Marx, “Capital”

“Marx forgot about supply and demand.”

This is a weird myth as supply and demand existed before Marx and in fact even is part of Adam Smith’s analysis. Supply and demand alone cannot explain prices. They only can explain relative fluctuations in prices. Fluctuations in supply and demand can tell you the direction prices will move, either up or down. But up and down from what? Relative prices alone cannot be used to predict prices.

“If, then, the supply of a commodity is less than the demand for it, competition among the sellers is very slight, or there may be none at all among them. In the same proportion in which this competition decreases, the competition among the buyers increases. Result: a more or less considerable rise in the prices of commodities. It is well known that the opposite case, with the opposite result, happens more frequently. Great excess of supply over demand; desperate competition among the sellers, and a lack of buyers; forced sales of commodities at ridiculously low prices. But what is a rise, and what a fall of prices? What is a high and what a low price? A grain of sand is high when examined through a microscope, and a tower is low when compared with a mountain. And if the price is determined by the relation of supply and demand, by what is the relation of supply and demand determined?”

— Karl Marx, “Wage-Labour and Capital”

You need some fixed point, an absolute price, to actually make any predictions. Supply and demand explain relative fluctuations in price around the value, but LTV holds that the equilibrium point between supply and demand is the same as the value. That is to say, price and value are not the same, prices fluctuate around values based on supply and demand. The reason a car is more expensive than an apple is not arbitrary. A car is way more complex and requires way more labor to produce than an apple. There are indeed arbitrary fluctuations in prices, but on a macroeconomic scale, they still have a tendency to fluctuate around their value.

“You would be altogether mistaken in fancying that the value of labour or any other commodity whatever is ultimately fixed by supply and demand. Supply and demand regulate nothing but the temporary fluctuations of market prices. They will explain to you why the market price of a commodity rises above or sinks below its value, but they can never account for the value itself. Suppose supply and demand to equilibrate, or, as the economists call it, to cover each other. Why, the very moment these opposite forces become equal they paralyze each other, and cease to work in the one or other direction. At the moment when supply and demand equilibrate each other, and therefore cease to act, the market price of a commodity coincides with its real value, with the standard price round which its market prices oscillate.”

— Karl Marx, “Value, Price, and Profit”

Claiming supply and demand determine prices is circular reasoning. Let’s give an example. The supply is 100 units and the demand is 100 units. I drop the the supply to 50. Now, from that data alone, tell me what the price would be. What? You can’t do it? That’s not enough data? Obviously. I don’t get why people unironically claim that this is enough data on its own to calculate prices.

But it gets even worse than this. Let’s say, after the change in supply, you have a price of $25. Now let me ask you: did the price go up or down? Again, you can’t tell me, because I did not give you the original price. So you can’t know if prices went up or down.

If you knew the base price was, let’s say, $50, and you increased decreased the supply, all this would tell you is that the price would likely increase. But without knowing the base price and having some prior knowledge on how the supply and demand curves look in that particular industry, you cannot predict what the new price would be.

Meaning, you have to at least have one measurement of price before you can make price predictions. Saying something that requires measuring price is what determines price is circular reasoning. Supply and demand can determine relative fluctuations in price, whether they’d go up or down, but cannot solely determine price.

“You can’t empirically measure value.”

Sure you can. It just requires adding up all the labor time that goes into producing a commodity all the way down the supply chain, and averaging it for all qualitatively similar commodities, and then comparing it to the average market price of that commodity. While values and prices are not the same, they should at least on a macroeconomic scale correlate one to another. I explain in this post here how you can actually do the math if you possess the economic data. Acquiring the data is the hard part, doing the math with the data is easy.

“It has never been empirically measured.”

There are tons of peer-reviewed studies that have attempted to measure it and showed the correlation between value and prices. Here are three listed below.

“…the results of the studies we cited above, in combination with the results on the structure of prices in the Greek economy, provide substantial evidence for the empirical strength of the labour theory of value. The latter appears to be a very useful analytical tool for the study of the behavior of a typical capitalist economy.”

— “Values, prices of production and market prices: some more evidence from the Greek economy”, Cambridge Journal of Economics

“…we have been able to confirm the work of Shaikh, Petrovic and Ochoa in demonstrating the validity of the classical labour theory of value.”

— “Testing Marx: Some new results from UK data”, “Capital & Class”

“…results have shown that the labour theory of value has strong empirical support.”

— “Correspondence Between Labor Values and Prices: A New Approach”, Review of Radical Political Economics

“Orthodox economics universally reject LTV.”

The appeal to “orthodoxy” has always come off as strange to me when what counts as “orthodoxy” differs from country-to-country. Marxian political economy is still taught in schools in China, which is the largest economy in the world. If you read peer-reviewed economic journals from China, economic problems are still approached from a Marxian economic perspective.

A left-wing critique might say “China bad.” You may hate it all you want, but fundamentally, that is not an argument. “Orthodoxy” simply implies whether or not it is held commonly, not whether or not you agree with its particular interpretation. Even if you dislike China’s interpretation, the fact it is held commonly here is evidence against this claim of “orthodoxy.”

A right-wing critique, on the other hand, also tend to claim China is not “true” Marxism and as well, arguing that they abandoned it in the late 1970s. There is a strange myth in the west that China abandoned Marxian economics after Mao died, when it was quite the opposite. Chinese economists in fact accused Mao of diverting from Marxian economics, and the market reforms in fact were more justifiable through Marxian economics than Mao’s economic policies. Mao may have been a genius in many things, but you cannot master everything. There were economic mistakes made. The insistence on tying the entire Marxian economic school to Mao’s policies personally makes little sense. I discuss this in more detail in this post.

One of the leading economists in China is professor Hong Yinxing.

Professor Hong Yinxing was born in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province in 1950. He obtained his Master Degree of Economics from Nanjing University in 1982 and his Ph.D. of Economics from Renmin University of China in 1987. He became a professor of Economics in 1989 and a distinguished professor of Humanities and Social Sciences in 2014. He had been serving as Chancellor of Nanjing University from 2003 to 2014 and was elected President of the University Affairs Council of Nanjing University in 2014. He is also the Vice-Chair of the Social Science Commission of the Ministry of Education, Chief Consultant to the Marxism Study Project of the Central Committee of CPC, and a representative of both the 17th and 18th National Congresses of CPC. Besides, he serves as Deputy Chief Editor of The Economist and Vice- Chair of the Chinese Society for Research on The Capital.

An economist with strong interdisciplinary interests in economic operation mechanism, economic development and macro-economy, Professor Hong Yinxing is the author of many publications. He has obtained special awards from the Ministry of Education and the Central Government for his academic achievements. In 1987, he was awarded The Sun Yefang Prize in Economics, and in 1991 the title of “Chinese Doctorate Holder with Outstanding Achievements” by the State Education Commission of China. He visited the United States as Fulbright Distinguished Scholar in 2000 and was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Law by the University of Waterloo in Canada in 2009. He was also selected as one of the “Top 100 Most Influential Economists on China’s Sixty-Year Economic Development” in 2009.

Source: Nanjing University’s website — Hong Yinxing

In one of his most well-known books, he references Marx 44 times and is only 243 pages long, meaning on average, 1 out of every 5.5 pages references Marx. The book isn’t even about Marx, but just China!

“A number of theories have been developed from China’s economic transformation…These new theories are consistent with the fundamental core of Marxist economics, reflecting changing realities in Chinese society today.”

— Hong Yinxing, “The China Path to Economic Transition and Development”

He also edits a peer-reviewed economic journal called China Political Economy where Chinese economists publish in it from all around China. It is published as two issues per year, and its most recent issue came out in July of this year. There are 12 papers in the most current 2020 issue. In looking at all 12…

- 5 do not reference Marx

- 5 directly uses Marx’s Capital or other economic works as a citation

- 2 talk about Marx or Marxism but no citations directly to Marx

Of course, you do not need to cite Marx in particular or even mention his name for the paper to be Marxian, in the same way you do not need to cite John Keynes personally or mention his name for a paper for be written from a Keynesian economic perspective.

The point is, Marxian economics is the norm in China. It is everywhere in China, schools, journals, books, television, etc. This paper here analyzes how it is taught in both public schools and in university — Teaching Marxist political economy in Chinese universities: why not earlier?

There was even a children’s book released that summarizes Marx’s Capital with illustrations and has received many rewards.

“The award-winning books were selected by the New Reading Research Institute, a non-profit research organization specialized in public reading, which recently received awards from the National Library. Nearly 1,000 children’s books published by over 100 publishing houses nationwide participated in the selection. Other awarded books include ‘Night at the Museum’ and ‘Our Chinese Characters.’”

— CGTN, “‘Das Kapital’ for children honored as among China’s top children’s books of 2018"

There was even a television show meant to teach people Marxian theory.

Appealing to “orthodoxy” makes little sense when the “orthodoxy” in China is Marxian economics, and it is the largest economy in the world. This is merely an appeal to “western orthodoxy” and not orthodoxy in general.

People who claim China abandoned Marxian economics by adopting market reforms tend to just reveal how incredibly ignorant they are of Marxian economics and equate it to some religion that asserts “public ownership = good.” This is, in fact, psychological projection, as the people who accuse Marxian economists of black-and-white thinking are the ones themselves who simply think “public ownership = bad, free markets = good.” In reality, it is way more complicated than this, and I explain how public ownership relates to Marxian economics here. Modern Marxian economics accepts both the efficacy of public planning and markets, but under different conditions.

The idea of using markets did not originate with China but Soviet economist Nikolai Bukharin proposed a very similar system to China in the 1920s-1930s, Marxian economist Rudolf Hilferding proposed a similar system back in 1910, and Marx himself seems to have envisioned a similar system to this as well, as even in his Manifesto he calls for only an “extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State” alongside a gradual (“by degree”) transition of private into public ownership alongside rapid development of the economy (“increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible”). Does that not sound like China’s system?

I tend to get the impression that those who insist that China abandoned Marxian economics — despite the fact this claim is objectively and observably false and simply talking to a Chinese person they will inform you that they were taught Marxian economics in school —often just assert this as a way to maintain western dignity. China is surpassing the west in many fields, and so rather than asserting their system is superior like they did to the Soviet Union, they instead try to insist that China’s system is actually the same as the west’s, so therefore it only further proves the west’s system is superior. In other words, it is a coping mechanism.

The point is, appealing to “orthodoxy” is hardly an argument when it is only western orthodoxy. The idea that we can dismiss the entirety of the economic theories from the largest economy in the world just because western countries don’t agree with them is fundamentally not an argument.

“Many things clearly have a difference between price and value, such as an artist’s signature.”

It is important to note that LTV only applies to commodities within a competitive market. The stronger the market competition, the more LTV applies. There is no market competition for an artist’s signature because it is monopolized by the artist themselves. I cannot start a business producing signatures for Jack Black. That defeats the entire purpose, the reason people want them is because they must come from Jack Black himself, who maintains a monopoly. Monopoly prices are always higher than their value.

“Commodities which are monopolized, either by an individual, or by a company, vary according to the law which Lord Lauderdale has laid down: they fall in proportion as the sellers augment their quantity, and rise in proportion to the eagerness of the buyers to purchase them; their price has no necessary connexion with their natural value: but the prices of commodities, which are subject to competition, and whose quantity may be increased in any moderate degree, will ultimately depend, not on the state of demand and supply, but on the increased or diminished cost of their production.”

— David Ricardo, “On The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation”

Imagine if the entire economy was run according to the principle of “artist signatures.” Imagine every commodity was monopolized by a single producer and a single producer alone. You could only buy bread from John Bread. You could only buy video games from Kim Game.

Would a society like this be able to allocate resources efficiently? Not even neoclassical economists would believe in such an absurd proposition. Of course this kind of arrangement would lead to an enormously inefficient economy because everything would be subjected to completely arbitrary prices with no connection at all to their cost of production.

“Wine gets more expensive the older it gets.”

Three easy explanations for this.

First, the older it gets, the more labor has to be expended to maintain the wine. This is not too hard to imagine. Storage is not completely labor-free. The maintenance of the storage building and checking on the wine itself does require some labor.

Second, land is always monopolized, meaning people have to pay a monopoly price, that being rent. Rent in LTV is caused by monopoly prices. The reason it is called “rent” is because it produces a price above its value, and thus, a person can “rent” the means to produce that commodity out to some other business, and that business can maintain regular profits while the renter can extract that surplus profits. Land itself becomes very quickly monopolized and thus typically tends to afford rent.

“The rent of the land, therefore, considered as the price paid for the use of the land, is naturally a monopoly price. It is not at all proportioned to what the landlord may have laid out upon the improvement of the land, or to what he can afford to take; but to what the farmer can afford to give.”

— Adam Smith, “The Wealth of Nations”

The rent resolves itself into the price of the commodity. It is a monopoly price on the commodity. Even if there is no one “renting out” the means to produce that commodity, the rent still exists, it would just mean that the business that produces the commodity collects both profits and rent. The two would likely be conflated and all treated as profits, but from an LTV perspective, they would more accurately be divided as two different sorts of revenue.

“When those…different sorts of revenue belong to different persons, they are readily distinguished; but when they belong to the same they are sometimes confounded with one another, at least in common language. A gentleman who farms a part of his own estate, after paying the expense of cultivation, should gain both the rent of the landlord and the profit of the farmer. He is apt to denominate, however, his whole gain, profit, and thus confounds rent with profit, at least in common language.”

— Adam Smith, “The Wealth of Nations”

The reason why monopoly price here is important is because the more wine is aged, the more difficult it becomes to age it. Aging wine for a few years is fairly trivial, but over a hundred years is not. The barrier of entry for a company producing century-old wine would be astronomical, it would require a century before the business could even turn a profit.

The older the wine, the more one would predict this monopolistic effect would take place. Extraordinarily old wine would thus be expected to have a significant monopoly price as well. Wine that is only a few years old would not have as much of one.

The third reason would also have to do with rent and monopoly prices. The value of a commodity is not simply the labor directly expended on its production, but the entire supply chain. If somewhere in the supply chain there is a monopoly, this will increase the price up through the supply chain. Land is typically monopolized and thus affords a rent, which would cause commodities that rely on land to become more expensive.

“The rise in marginal costs caused by the rise in land rent…land factor tends to form monopoly markets, and monopoly will generally lead to distortion of resource allocation. Under the nonpublic land ownership system, there will be monopolies in the two markets of ‘industrial land’ and ‘commercial land.” Therefore, there will be greater efficiency distortion and welfare distortion’ than the baseline model of monopoly in the market of ‘commercial land.’”

— “How the land system with Chinese characteristics affects China’s economic growth — an analysis based on a multisector dynamic general equilibrium framework”, China Political Economy

All commodities would likely have some increase in price caused by rent, but this is typically negligible for most commodities. Most commodities are produced in large amounts fairly quickly. If, for example, I have to spend $1,000 of rent per month but within that month I produce 10,000 toys, then each toy will only be affected by rent prices by about $0.10. Some commodities are also produced very slowly, like cars, but rent is still negligible because these tend to have very high labor costs associated with them. Let’s say only ten cars per month can be produced on this land, but each car will cost $25,000. Therefore, the rent is still negligible, as adding $100 to this price per car is hardly noticeable.

However, if I am producing 100 bottles of wine over ten years, then each bottle will be affected by rent by $100. Aged wine tends to not be produced in very large quantities as it is often produced at home in personal cellars, and its age causes rent to affect its cost significantly more than what is expected of most commodities. Anything that is produced in small amounts over long periods of time should have a divergence of its price from its value.

“Fiat money disproves LTV.”

Fiat money is fairly easy to explain using even Adam Smith’s simple LTV. I go into detail on this in this post. In simple terms, fiat money, is, again, a monopoly price. Money ceased to actually represent the value of gold even before fiat money. Once it becomes a global currency, it ceases to represent gold anyways. All money needs to do is symbolically represent a consistent value of gold, since it is simply a wheel used for transactions, and gold in particular is not important. Once a general price of money has been established, it can be enforced and maintained by the state monopoly on the production of the currency, keeping up its price as a monopoly price. If LTV is correct, then fiat money’s price relies on the state maintaining a monopoly over the production of money. If the state allowed anyone to print money, then its price would quickly collapse.

“The transformation problem debunks LTV.”

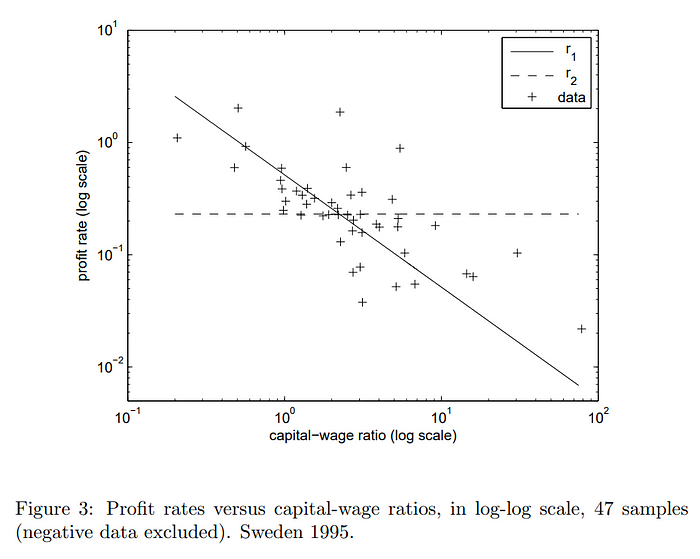

The transformation problem is caused by two conflicting assumptions in Marxian economics: LTV and profit equalization. Both are ideas that even Adam Smith argued for. Profit equalization is simply the idea that in a perfectly competitive economy, business would go where the profits are and leave where the profits aren’t, causing profits to equalize across the economy. Marx showed that LTV demonstrates that profitability would inherently be tied to the organic composition of capital, that is, the ratio of investment spent on machines over human labor. This is also sometimes known as capital intensity.

The organic composition of capital would tend to equalize within a single industry since everyone would try to adopt the best machines, but it fundamentally cannot equalize across industries. Cellphone manufacturers can’t adopt the same machines that cheese burger producers have. It makes no sense. So one would naturally conclude that they would have different levels of profitability, which contradicts with profit equalization.

Marx thought these could be made to agree with a mathematical transformation to convert values into “prices of production” which would make the two assumptions line up. He tried to find this mathematical transformation and never could. It took about a century later for mathematics to advance enough so that various mathematicians were able to prove that such a transformation did not exist. Marx could not have figured this out on his own as it required mathematics that did not exist for another century.

Both LTV and profit equalization therefore contradict. Does this prove LTV is wrong? No. Just because two things contradiction, does not mean they are not real, as contradictions can actually exist in the economy. There are two possibilities here, either one of the two premises are wrong, or both are correct but operate as opposing “forces” in the economy, so to speak. LTV would “pull” prices to their values, profit equalization would “pull” prices to their prices of production, and empirically, we would thus expect to find results somewhere in between the two.

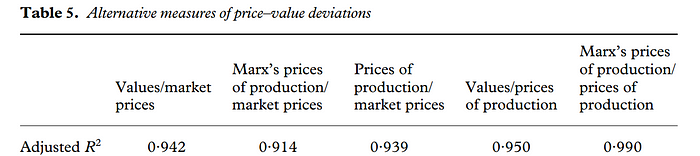

Let’s start with the first case. If LTV is wrong, then empirically, we should measure profits across industries are all roughly the same. If profit equalization is wrong, we should empirically measure that profits differ by their organic compositions of capital (or capital intensity). So which is true? It is LTV. The negative correlation between organic composition of capital and prices has been shown through various studies.

“This paper confirms the main results of previous studies concerning labour values and market prices. It is shown that both the labour theory of value and the neo-Ricardian theory yield very good results in explaining data. Differences in estimated outcomes are insignificant. Therefore, approving the approaches developed by Shaikh (1984) and Farjoun and Machover (1983) and having Occam’s razor in mind, we should prefer the labour theory of value for analysing real world phenomena. In addition, a critical point for neo-Ricardian theory emerges: the basis of the transformation debate seems to be fallacious because profit rates and capital intensity are negatively correlated.”

— “Labour values, prices of production and the missing equalisation tendency of profit rates: evidence from the German economy”, Cambridge Journal of Economics

Let’s take a look at the second case. It is possible that LTV and profit equalization are both true to a degree, and the actual results lie somewhere in between the two.

“The LTV is a ‘deeper’ theory than the TPP, yet its predictions are just as close, if not closer, to the observed reality of capitalism. Through the stochastic melee of the market, the set of prices predicted by the LTV provides one pole of attraction, while the set of prices of production provides another.”

— “Does Marx Need to Transform?”, Marxian Economics: A Reappraisal

This latter paper provides more economic data to confirm that profits do indeed not equalize but as LTV predicts, they diverge based on organic composition of capital. However, they also argue that there does appear to be a somewhat small divergence in prices, not enough to offset the profit trend but enough to be observed. Which provides some evidence for the claim that both laws are operating at the same time.

Either way, there seems to be very little evidence to suggest that profit equalization triumphs over LTV. The predictions of LTV seem to hold very strongly. The transformation problem is hardly a “problem” at all, a mathematical transformation between value and prices is not necessary. Both are equal and opposite “forces” in the economy, pulling the prices one way or the other, however, profit equalization provides an incredibly small, hardly measurable pull. LTV without profit equalization is a fairly accurate prediction on its own. The claim that profit equalization is correct but LTV is not does not fit the empirical evidence.

In fact, here is a third paper showing the lack of empirical evidence for profit equalization, but even further evidence for LTV.

“The results are broadly consistent; labour values and production prices of industry outputs are highly correlated with its market price. The predictive power is compared to alternative value bases. Furthermore, the empirical support for profit rate equalisation, as assumed by the theory of production prices, is weak.”

— “Labour value and equalisation of profit rates: a multi-country study”, Dave Zacharia

Again, the empirical evidence is just simply on the side of LTV.

“The Soviet Union dissolving proved the LTV is false.”

This is a weird claim I’ve heard a few times. LTV is a theory of market economies. The USSR was a planned economy. It is like saying the abolition of slavery in the US proves Keynesian economics to be false. One is not related to the other.

“Mises’s economic calculation problem disproves LTV.”

The ECP applies specifically to planned economies, so it fails for the prior reason. However, the ECP is inherently an argument based in circular reasoning as well. Imagine a train needs to go from point A to point B and there is a mountain in the way. Do you go around it or straight through it? Mises would tell you that the only way you can decide is through markets, which provide rational prices and therefore decide the most economically efficient and profitable way.

However, there are two slights of hand here. First, markets decide prices, and so this allows the company to make the most rational decision based on price mechanisms. But the decision he makes will be the one that is the most profitable to him directly, not necessarily the cheapest. It may be more profitable to go around the mountain since it would cost less, but the marginal costs of all commodities would be reduced due to decreased transportation cost if he went through it. This might be less profitable, but it would increase everyone else’s profits and over a few decades likely more than make up for the cost. The business, however, does not make the most rational decision, because prices are not what determines his decisions, but profits, which are not rational.

The equating of market decision to “rationality” is circular, it assumes the conclusion from the get-go. Markets are not rational. The ECP only proves that the decision would not be made according to market mechanisms, not that it would not be rational. Of course, this is not surprising, obviously the decisions would not be made according to markets. That is, in reality, what the ECP says. It states the obvious, but with a slight of hand, pretends it made a deep point.

The second slight of hand is assuming that prices can only be determined with market mechanisms. This only works within a framework that rejects LTV. Meaning, it can’t be used as an argument against LTV. You basically have to assume LTV is false in order to conclude the ECP is a valid argument, since there is no reason price mechanisms would not exist in a planned economy from an LTV perspective. Hence, the ECP is circular as an argument against LTV. It only works as an argument against planned economies if you already buy into neoclassical economics.

“The consumers and producers decide the prices based on their subjective opinions, so it makes no sense to say it is determined by labor.”

Apple will never sell their iPhones for $5. They would go bankrupt since the cost of production is astronomically higher than this. Apple will also never sell iPhones for $5 billion. Because the cost of production is so much lower that they would just be out-competed by people selling it at a reasonable price.

Subjective theory of value fails by treating transactions between two people as if they’re completely isolated from the rest of the economy. A producer must take into account their production cost and market competition, independent of their own free will. If they don’t, they get kicked out of the market through being out-competed and go bankrupt. The businesses that exist, therefore, are businesses that obey unspoken economic laws, against their own free will.

When you recognize this, subjective theory of value quickly falls apart. Since there is clearly more that goes into determining prices than simply whatever people’s personal opinions on what prices should be are. In a competitive economy, prices will be driven down by competition, but there is a definite minimum at cost of production. So we would only expect they would correlate to some value related to the cost of production, independent of what people’s personal opinions on what that value should be.

Simply pointing out the obvious, that transaction happen between two people, does not disprove the fact that on a macroeconomic scale, prices may still follow certain economic laws. Each producer has to react to the society he produces within, he lacks full control over his own business as it must survive in a competitive marketplace. This requires him to make specific decisions, and these decisions cannot be arbitrary.

“According to the marginal utility theory, the value (exchange value) of any material good is determined by its marginal, i.e. its minimum utility. By the utility of things the authors of this theory understood not the objective property of commodities to satisfy some particular social need in the actual conditions of commodity production, but their subjective psychological evaluation by people in the unusual circumstances in which they possessed a certain stock of some material goods and could not freely reproduce or exchange them for other goods. The subjective theory of value ignores the social character of production, denies the existence of objective economic laws and depicts each producer of material goods as a man living in complete isolation from society.”

— G. A. Kozlov, “Political Economy: Capitalism”

Marginal utility theory, as shown by various economists, can lead to a mathematically consistent economic theory. But the problem is, the mathematics do not point to anything real. The fact the theory is mathematically consistent does not demonstrate its validity. “Utility” as a quantitative measure is a vague, ethereal idea that floats in the back of people’s minds, with no connection to the real world, and almost seems like it’s a real thing if you don’t think about it hard enough. It is what is known as a “floating abstraction.”

“Do diamonds have value because we labor for them? Or do we labor for them because they have value? Something has to be valued as an object of utility first before anyone will labor for it, therefore, it is utility that determines value.”

This argument, which I have heard many times, manages to squeeze two logical fallacies in it at once. The first being conflation, and the second being post-hoc ergo propter hoc.

To start with the former, valuing something as an object of utility is its use-value, while what it sells for on the market is its exchange-value. While it is true something must have a use-value before anyone will labor for it, simply viewing something as an object of utility tells you nothing of the actual cost that will go into producing it. This information can only be provided to the producer after they labor for it, after they attempt to produce it. Exchange-value necessarily can only be determined after labor is performed. This word game conflates the two types of value to make it seem like exchange-value is being determined beforehand, when it is not.

The second problem is assuming because one event came after the other, one event must’ve caused the other. In some sense, yes, you need use-value to exist before exchange-value can exist, they must come in this sequence. But does that mean use-value then determines exchange-value? Does that mean the utility of an object determines its price?

While utility could determine price, it is a logical fallacy to suggest just because A comes before B, A must’ve caused B. Millions of years of evolution had to occur before human economies could form in the first place. Therefore, evolution precedes all theories of value. Should we then conclude that it therefore must be evolution that determines value? As in, the price of commodities are determined by evolution simply because it must occur before anything can have a price at all? Obviously not!

Yet, this is how absurd this argument is. It conflates two forms of value with each other, and then asserts because one form comes first, it therefore must be cause of prices. This is an atrocious argument yet I have seen it multiple times.

“The capitalist creates value because he has to invest/risk his capital for workers to ever produce anything the first place.”

The labor theory of value deals with the creation of value. Value is related to — but not the same as — price. Again, just because something is a prerequisite to value does not mean it actually determines the quantitative magnitude of that value. Millions of years of evolution had to occur before human societies could ever produce anything with value at all. Do we need to include human evolution in our model of predicting prices? Again, obviously not. This is a a repeat of the post-hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. How do you quantify risk? How does it then translate into prices of commodities? If you believe you have a way to solve this, create a model for it, then do empirical research to see its predictive capabilities. So far, no one who makes this claim has even attempted to do so. I wonder why.

“The entrepreneur creates value by inventing new ideas.”

The Bayer process. Before this was invented, aluminum was an incredibly expensive metal. Afterwards, it is now one of the cheapest metals. Inventions tend to cause a declination in value, not an increase in it. People who make this claim, I assume they do not even know what a “theory of value” even is. Even marginal utility theory would agree with me here that the value declined of aluminum after the invention of the Bayer process. The increase in the quantity of aluminum produced reduced the marginal utility per unit and thus reduced its value. Believing that inventions create value would be an abandonment of both labor theory of value and the subjective theory of value. It is very strange that people even attempt to make this argument.